This Is Why Agra’s Architecture Will Blow Your Mind

You know that feeling when you see something so breathtaking, it stops you in your tracks? That’s exactly what happened when I first saw Agra’s skyline at dawn. More than just the home of the Taj Mahal, Agra is a living gallery of Mughal artistry. The symmetry, the inlay work, the sheer scale—it’s not just architecture, it’s poetry in marble and sandstone. This city doesn’t just tell India’s history—it embodies it in every carved arch and domed roof. From the quiet elegance of garden layouts to the imposing strength of fortress walls, Agra’s buildings are not merely structures—they are declarations of power, devotion, and beauty. To walk through its monuments is to step into a world where every stone has meaning, and every shadow tells a story.

The First Glimpse: Agra’s Skyline as a Work of Art

Arriving in Agra often begins with sensory overload. The city pulses with life—honking rickshaws, street vendors calling out, children darting between cars, and the warm scent of spices drifting from roadside stalls. Amid this vibrant chaos, the first view of Agra’s monuments feels almost surreal. There, rising above the dust and noise, stands the Taj Mahal, its white dome glowing like a pearl in the morning light. This contrast—between the ordinary rhythm of daily life and the extraordinary presence of architectural wonder—is part of what makes Agra unforgettable. The city does not hide its treasures behind museum glass; it lets them breathe alongside modern India.

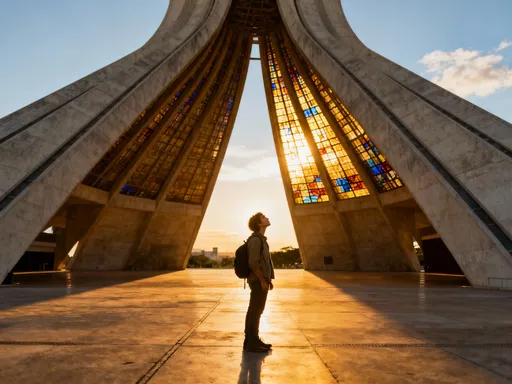

For many visitors, the most powerful moment comes at sunrise, when the first rays of sunlight kiss the marble surface of the Taj Mahal. At that hour, the monument appears to float above the Yamuna River, its reflection shimmering like a dream. The changing light transforms the building throughout the day—soft pink at dawn, blinding white at noon, golden at sunset, and ethereal under moonlight. This dynamic interplay of light and material is intentional. Mughal architects understood that beauty is not static; it shifts with time, weather, and perspective. The experience of seeing the Taj at dawn is not just visual—it is emotional, almost spiritual.

The setting itself plays a crucial role in shaping this experience. The Taj is framed by a long reflecting pool, flanked by cypress trees and garden pathways. This deliberate composition guides the eye and slows the pace of the visitor, creating a sense of anticipation. The approach is designed to build awe, much like the entrance to a temple or cathedral. The same principle applies to other monuments in Agra, where courtyards, gateways, and elevated platforms are used to control sightlines and emphasize grandeur. Understanding these design choices deepens appreciation. It reveals that Agra’s architecture was never just about building structures—it was about crafting experiences.

First impressions matter because they shape how we remember a place. In Agra, the initial sight of the skyline sets the tone for everything that follows. It signals that this is not an ordinary city. Here, history is visible, tangible, and deeply felt. Whether it’s the distant silhouette of Agra Fort or the unmistakable curve of the Taj’s dome, the city announces itself as a place of artistic mastery. For families visiting with children or couples traveling together, this moment of shared wonder can become a lifelong memory. It reminds us that beauty, when experienced in full presence, has the power to unify, inspire, and transform.

Mughal Mastery: The DNA of Agra’s Architectural Style

To understand Agra’s buildings is to understand the Mughal Empire, a dynasty that ruled much of the Indian subcontinent from the early 16th to the mid-19th century. The Mughals were not just conquerors—they were patrons of art, science, and culture. Their architecture reflects a unique fusion of influences: Persian elegance, Islamic geometry, and Indian craftsmanship. This blend created a style that is instantly recognizable—grand yet refined, intricate yet balanced. Agra became one of the empire’s most important centers, and its monuments stand as enduring testaments to this golden age of design.

Several key features define Mughal architecture. The most iconic is the onion dome—a bulbous, slightly pointed dome that crowns many of Agra’s buildings. This shape, inspired by Persian and Central Asian models, was both functional and symbolic. It allowed rainwater to run off easily while representing the heavens in spiritual terms. Another defining element is the iwan, a large vaulted portal often framed by decorative tile work or stone inlay. These gateways serve as grand entrances, marking the transition from the outside world into sacred or royal space. Minarets, tall slender towers typically placed at the corners of buildings, add vertical emphasis and were originally used for the call to prayer.

Equally important is the charbagh, a four-part garden layout that symbolizes the Islamic concept of paradise. Divided by water channels representing the four rivers of heaven, these gardens create a sense of order and harmony. At the Taj Mahal, the charbagh is perfectly aligned with the main structure, reinforcing the theme of balance. The use of symmetry is not accidental—it reflects both aesthetic ideals and spiritual beliefs. In Mughal thought, symmetry represented divine perfection, and the careful alignment of buildings with cardinal directions reinforced their cosmic significance.

Materials were chosen with equal care. Red sandstone and white marble dominate Agra’s skyline. Sandstone, locally quarried and easier to carve, was widely used in early Mughal constructions like Agra Fort. It conveys strength and permanence. White marble, imported from Rajasthan, was reserved for the most sacred or prestigious projects. Its smooth, luminous surface changes color with the light, giving it a living quality. The shift from sandstone to marble over time—from Akbar’s era to Shah Jahan’s—mirrors the evolution of Mughal aesthetics toward greater refinement and delicacy.

Every architectural choice reflected imperial power and spiritual devotion. The scale of the buildings was meant to inspire awe, reminding visitors of the emperor’s authority and connection to the divine. At the same time, intricate carvings and inlays demonstrated the empire’s wealth and access to skilled artisans. Calligraphy from the Quran adorned walls, blending art and faith. Even the placement of buildings along the riverbank was strategic, using natural elements to enhance beauty and symbolism. Together, these elements formed a language of architecture—one that spoke of order, harmony, and transcendence.

Taj Mahal: Beyond the Postcard, Into the Details

The Taj Mahal is one of the most photographed buildings in the world, but no image can capture its full artistry. Up close, the details reveal a level of craftsmanship that borders on the miraculous. The exterior walls are covered in pietra dura, a technique in which semi-precious stones—like lapis lazuli, jade, crystal, and turquoise—are inlaid into marble to form intricate floral patterns and geometric designs. Each piece is cut by hand and fitted so precisely that no grout is needed. The result is a surface that appears painted, yet is entirely made of stone. This technique, perfected under Shah Jahan, turned the Taj into a three-dimensional canvas of color and texture.

Equally impressive is the calligraphy that runs along the main gateway and exterior arches. Verses from the Quran are written in black marble inlaid into white stone, their size increasing slightly with height to maintain visual consistency from the ground. This optical correction, known as entasis, shows the architects’ deep understanding of human perception. The script itself is elegant and flowing, turning religious text into an integral part of the building’s beauty. The choice of verses—many of which speak of judgment, paradise, and divine mercy—adds a spiritual dimension, reminding visitors that the Taj is not just a monument to love, but also a gateway to the afterlife.

Symmetry is the soul of the Taj Mahal. The entire complex is laid out along a central axis, with identical buildings on either side, perfectly mirrored gardens, and minarets placed at exact intervals. This precision is not merely decorative—it carries deep meaning. In Islamic tradition, symmetry reflects the order of the universe and the perfection of God. The tomb at the center represents the soul’s journey toward divine unity. Even the placement of the Yamuna River behind the Taj enhances this balance, its reflective surface doubling the image and creating a sense of infinity.

One of the most ingenious features is the outward tilt of the four minarets. Each tower leans slightly away from the main dome. This was not a mistake, but a deliberate safety measure. In the event of an earthquake, the minarets would fall away from the tomb, protecting the central structure. This blend of aesthetic and engineering brilliance is typical of Mughal design. Other subtle details include the changing color of the marble at different times of day, the echo effect under the main dome, and the way shadows move across the inlay work as the sun travels. These are not accidents—they are part of a carefully orchestrated experience.

The Taj Mahal is often described as a symbol of love, built by Shah Jahan in memory of his wife Mumtaz Mahal. But it is also a sculptural masterpiece, a funerary garden, and a spiritual statement. It combines personal grief with imperial grandeur, human emotion with divine order. To appreciate it fully, one must look beyond the postcard image and study the details—the way light plays on stone, the precision of the inlay, the silence of the gardens. It is in these moments of quiet observation that the true depth of the Taj reveals itself.

Agra Fort: Where Power Met Aesthetics

Just 2.5 kilometers from the Taj Mahal stands Agra Fort, a massive red sandstone fortress that served as the main residence of the Mughal emperors. While the Taj represents spiritual and artistic ideals, the fort embodies political power and military strength. Yet even here, beauty was never sacrificed for function. The fort is not just a stronghold—it is a palace complex filled with courtyards, halls, and private chambers, each designed with aesthetic precision. Walking through its gates is like stepping into the private world of emperors, where governance and grandeur went hand in hand.

Two of the most significant structures within the fort are the Diwan-i-Am and the Diwan-i-Khas. The Diwan-i-Am, or Hall of Public Audience, was where the emperor met with common people and officials. Its open design, supported by rows of columns, allowed large crowds to gather while maintaining visibility and acoustics. The hall’s sandstone surface is carved with floral patterns and geometric motifs, showing that even administrative spaces were treated as works of art. The Diwan-i-Khas, or Hall of Private Audience, was reserved for nobles and foreign dignitaries. Here, the emperor sat on a marble throne platform, with the phrase “If there is paradise on earth, it is here, it is here, it is here” inscribed in calligraphy above. The room’s design—cool, quiet, and richly decorated—was meant to impress and intimidate.

One of the most striking features of the fort is the use of jali screens—delicate stone lattices that filter light and air while preserving privacy. These screens, found in royal chambers and balconies, are carved with intricate floral and geometric patterns. They allowed royal women to observe court proceedings without being seen, reflecting the customs of the time. The craftsmanship is astonishing—each jali is a single piece of stone, chiseled by hand into complex designs. These screens also served a practical purpose, reducing heat and creating natural ventilation in the hot climate.

The fort’s layout follows a hierarchical principle, with public areas near the entrance and private quarters deeper inside. The Khas Mahal, a palace overlooking the Yamuna River, was Shah Jahan’s private residence. From its balconies, he could see the Taj Mahal—the tomb of his beloved wife. It is said that in his final years, after being imprisoned by his son, he spent his days gazing at the monument, a silent witness to both his love and his loss. Standing in that same spot today, visitors often feel a deep emotional connection, not just to the architecture, but to the human stories embedded within it.

Fatehpur Sikri: The Ghost City of Architectural Experimentation

A short drive from Agra lies Fatehpur Sikri, a deserted city built by Emperor Akbar in the late 16th century. Unlike the Taj or Agra Fort, this site was abandoned within just 14 years, making it a rare example of a preserved imperial capital frozen in time. The reasons for its abandonment are debated—some say water shortages, others cite strategic concerns—but its legacy endures. Fatehpur Sikri is a laboratory of Mughal architectural innovation, where Akbar experimented with blending Islamic, Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist styles into a new, syncretic vision.

The most imposing structure is the Buland Darwaza, the “Gate of Magnificence,” built to commemorate Akbar’s victory in Gujarat. Soaring over 50 meters high, it is one of the largest gateways in the world. Its surface is covered in red sandstone with intricate carvings and Quranic inscriptions. The climb up the central staircase is symbolic—each step represents a stage in the spiritual journey. The gate’s scale was meant to overwhelm visitors, reinforcing the emperor’s divine authority. Yet, even in its grandeur, the design incorporates Indian elements, such as chhatris (domed kiosks) and corbelled arches, showing Akbar’s respect for local traditions.

Another highlight is the Panch Mahal, a five-story pavilion designed for relaxation and entertainment. Each level decreases in size, creating a stepped pyramid effect. The top floor, open to the sky, was reserved for the emperor. The entire structure is supported by intricately carved columns, some shaped like lotus stems, blending natural motifs with architectural function. The building was not just beautiful—it was practical, allowing cool breezes to circulate and offering panoramic views of the city.

Fatehpur Sikri also includes the Jama Masjid, one of the largest mosques in India, and the tomb of Sufi saint Salim Chishti, whose blessings Akbar believed led to the birth of his son. The tomb, made of white marble, is a precursor to the Taj Mahal in both style and spiritual significance. Its jali screens are among the finest in India, with patterns so delicate they appear woven from stone. The emotional aura of the place is palpable—quiet, reverent, and timeless. Visitors often speak of a sense of peace, as if the city, though abandoned, still holds the echoes of prayer and contemplation.

Hidden Details: What Most Visitors Miss

Most tourists spend a few hours at the Taj Mahal, snapping photos before moving on. But the true artistry of Agra’s architecture reveals itself only to those who slow down. Many details go unnoticed—the way shadows dance across carved walls at noon, the reflections of domes in still pools, the acoustics that allow a whisper to carry under a dome. These are not accidents; they are intentional design choices meant to engage the senses.

One overlooked feature is the use of light and shadow. Mughal architects understood how sunlight moves throughout the day. At certain hours, the interplay of light through jali screens creates intricate patterns on floors and walls, turning interiors into living canvases. In the Diwan-i-Khas, the marble inlay catches the sun at specific angles, making the flowers appear to glow. Similarly, the water channels in charbagh gardens are aligned to reflect the sky and buildings, doubling the visual impact.

Acoustics were also carefully considered. Under the central dome of the Taj Mahal, a single clap can produce multiple echoes, a phenomenon that fascinated early visitors. In Fatehpur Sikri’s Diwan-i-Khas, the layout allows a whisper from the emperor’s throne to be heard clearly at the back of the hall—a clever use of sound for both practical and symbolic purposes. These features remind us that Mughal architecture was not just about appearance—it was about experience.

To truly appreciate Agra, visitors should return at different times of day. Early morning offers soft light and fewer crowds. Late afternoon brings golden hues and long shadows. Evening, especially during the full moon, transforms the Taj into a luminous silhouette. Even the gateways and pavilions, often rushed past, deserve attention. Their carvings tell stories—of battles, of faith, of daily life. Taking time to look, to listen, to feel the cool stone under hand, creates a deeper connection. It turns a sightseeing trip into a journey of discovery.

Preserving the Art: Challenges and Efforts in Agra Today

Agra’s monuments face serious threats. Air pollution, largely from nearby industries and vehicle emissions, has caused the white marble of the Taj Mahal to yellow over time. In the 1990s, the Indian government established the Taj Trapezium Zone, a 10,400-square-kilometer area around the monument where industrial activity is restricted. Factories using coal were either relocated or required to switch to cleaner fuels. While these measures have helped, the battle against pollution is ongoing.

Overcrowding is another challenge. Millions of visitors each year put pressure on the structures and surrounding environment. To manage this, ticketing systems now limit daily entries, and designated pathways protect fragile surfaces. Conservation teams regularly clean the marble using a special clay pack treatment that draws out pollutants without damaging the stone. Experts from the Archaeological Survey of India work alongside international organizations to monitor structural integrity and prevent water seepage, which can weaken foundations.

UNESCO, which designated the Taj Mahal a World Heritage Site in 1983, plays a vital role in preservation. Its guidelines ensure that any restoration work respects the original materials and techniques. For example, when repairing inlay work, artisans use the same types of stones and hand-carving methods as the Mughals did. This commitment to authenticity means that conservation is not just about fixing damage—it is about honoring the original vision.

Responsible tourism is key to the future of these monuments. Visitors can help by following rules—no touching the marble, no littering, no climbing on structures. Choosing guided tours that emphasize education over speed supports sustainable practices. Supporting local artisans who continue traditional crafts, such as stone inlay and jali carving, also contributes to cultural preservation. When travelers slow down, pay attention, and treat these sites with reverence, they become part of the effort to protect them.

Conclusion

Agra isn’t just a destination—it’s an immersion into a world where architecture is art. Every structure tells a story of vision, skill, and cultural fusion. From the ethereal beauty of the Taj Mahal to the imperial strength of Agra Fort and the experimental spirit of Fatehpur Sikri, the city offers a journey through time and imagination. By understanding the details—the symmetry, the materials, the hidden craftsmanship—we don’t just see monuments—we connect with the souls who built them. The real magic? Realizing that beauty this profound can still speak across centuries. You don’t just visit Agra. You feel it. And in that feeling, there is a quiet invitation: to look closer, to listen more deeply, and to carry that sense of wonder into everyday life.