You Won’t Believe What’s Hiding in Canberra’s Urban Landscape

Canberra isn’t just Australia’s capital—it’s a secret playground of bold, unexpected architecture. I went in expecting politics and monuments, but instead found futuristic curves, daring designs, and buildings that look like they’re from another planet. From the gravity-defying canopy at the Museum of Australia to the quiet brilliance of hidden pavilions, this city surprised me at every turn. If you think Canberra is just bureaucracy, think again—its architectural soul is anything but ordinary.

Reimagining Canberra: Beyond the Political Postcard

Most people picture Canberra as a city of suits, roundabouts, and orderly grids—a planned capital built for function, not flair. Yet beneath this surface lies a deeply artistic foundation. From its inception, Canberra was never meant to be merely administrative. The original 1912 plan by American architects Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin envisioned a city harmonized with nature, where landscape and architecture would coexist in poetic balance. Their design featured sweeping lake systems, geometric vistas, and ceremonial axes that connected key institutions through visual and symbolic alignment. This was not urban planning by committee—it was urban poetry.

Today, that visionary spirit continues to shape Canberra’s evolution. While other capitals grow chaotically, Canberra expands with intention. Each new structure is considered within the broader context of the city’s master plan, allowing for innovation without sacrificing coherence. This deliberate pace has created space for architectural experimentation that feels both bold and grounded. The city does not rush toward trends; instead, it absorbs them thoughtfully, ensuring that every addition contributes to a larger narrative. As a result, Canberra has become a living laboratory of public architecture—where form follows meaning, not just function.

The Parliamentary Triangle, anchored by Parliament House, the High Court, and the National Gallery, exemplifies this balance. Its layout is more than logistical—it’s symbolic. The placement of buildings along cardinal lines reflects democratic ideals of transparency and order. Yet within this structured framework, architects have found room to innovate. Modern interventions respond to the Griffin plan not by rejecting it, but by reinterpreting it. This dialogue between past and present makes Canberra unique among world capitals. It is a city that remembers its origins while confidently stepping into the future.

The Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House: History Wrapped in Heritage

Standing at the heart of the Parliamentary Triangle, Old Parliament House is a masterclass in restrained elegance. Completed in 1927, the building was designed in the stripped classical style—a minimalist interpretation of Greco-Roman architecture that reflects the dignity and sobriety of democratic institutions. Its symmetrical façade, colonnaded entrance, and central dome project stability and continuity. At the time of its construction, it was not considered avant-garde, but rather a deliberate choice to anchor Australia’s young democracy in timeless visual language.

What makes this building significant today is not just its historical role—housing Australia’s federal parliament for over six decades—but how its preservation informs contemporary architectural discourse. Rather than being demolished or repurposed invisibly, the structure was transformed into the Museum of Australian Democracy, a space dedicated to civic education and public engagement. This adaptive reuse honors the building’s legacy while giving it new relevance. Visitors walk through the same chambers where landmark legislation was debated, now enhanced with interactive exhibits that connect past decisions to present-day citizenship.

The contrast between Old Parliament House and the modern Parliament House atop Capital Hill is striking. The latter soars with sweeping curves and a grass-covered roof that blends into the landscape, symbolizing openness and accessibility. Yet the quiet presence of the older building remains powerful. It serves as a reminder that architectural progress does not require erasure. In fact, Canberra’s layered identity—where heritage and innovation stand side by side—gains depth from this coexistence. The preservation of Old Parliament House is not nostalgia; it is a conscious decision to maintain continuity in a city built on long-term vision.

National Museum of Australia: Where Architecture Tells a Story

If Old Parliament House speaks in hushed tones of tradition, the National Museum of Australia shouts in a bold new dialect of form and meaning. Designed by the renowned firm Ashton Raggatt McDougall and opened in 2001, the building is a fragmented composition of curved walls, tilted planes, and intersecting volumes. Its exterior resembles a jigsaw puzzle assembled with deliberate disarray, challenging visitors to make sense of its pieces. This intentional complexity is not mere spectacle—it is narrative architecture. Every angle, material, and spatial shift reflects a chapter in Australia’s diverse and often contested history.

One of the most discussed features is the “knot,” a circular void at the building’s center where walkways converge. Symbolically, it represents the idea of national unity—not as a fixed point, but as an ongoing negotiation. The surrounding walls are clad in materials that reference different regions and cultures: copper for mining heritage, timber for colonial settlements, and ochre-colored panels echoing the outback. Even the building’s orientation aligns with significant geographical and cultural markers, reinforcing its role as a physical embodiment of national identity.

Upon its unveiling, the museum’s design sparked intense debate. Critics called it chaotic, even alienating. Supporters praised its courage to break from convention and reflect the complexities of Australian society. Over time, public perception has shifted. What once seemed jarring now feels authentic. The building does not offer easy answers; instead, it invites curiosity and conversation. For families visiting with children, the museum’s dynamic spaces create an engaging environment where architecture itself becomes part of the learning experience. Interactive displays, open galleries, and changing light conditions keep the atmosphere fresh and immersive.

The National Museum proves that public buildings can be both functional and deeply expressive. It accommodates large crowds, rotating exhibitions, and educational programs without sacrificing its artistic integrity. More importantly, it sets a precedent: architecture in Canberra does not have to play it safe. When done with purpose, even controversial designs can grow into beloved landmarks. The museum stands not as an anomaly, but as a statement—Canberra is a city willing to take architectural risks when they serve a greater story.

Australian War Memorial Expansion: Blending Past and Future

The Australian War Memorial is one of the nation’s most sacred sites, a place of remembrance, reflection, and education. Its original structure, completed in 1941, is a dignified example of interwar classical architecture—symmetrical, solemn, and rooted in tradition. The Hall of Memory, with its mosaic dome and eternal flame, commands reverence. For decades, the memorial stood largely unchanged, its power lying in its stillness. But as visitor numbers grew and Australia’s military history expanded to include more recent conflicts, the need for thoughtful expansion became clear.

The current redevelopment project, one of the largest in the memorial’s history, approaches this challenge with remarkable sensitivity. Rather than constructing a new building that competes with the original, the design team has chosen to extend underground. New galleries, educational spaces, and visitor facilities are being carved beneath the existing landscape, preserving the visual integrity of the memorial’s façade and the Anzac Parade vista. This subterranean approach ensures that the skyward silhouette of the memorial remains untouched—a crucial detail for a site so tied to national symbolism.

At the same time, the expansion introduces modern architectural elements in subtle but meaningful ways. Natural light filters into underground spaces through carefully positioned shafts and courtyards, creating moments of quiet illumination that enhance the contemplative mood. Materials have been selected for their durability and emotional resonance—stone, bronze, and warm-toned concrete echo the gravitas of the original structure while signaling a new era. The design also improves accessibility, ensuring that visitors of all ages and abilities can engage fully with the memorial’s offerings.

This balance of reverence and renewal is no small feat. The project demonstrates how national monuments can evolve without losing their soul. In a world where change often means replacement, Canberra’s approach is refreshingly patient. The War Memorial expansion is not about erasing the past, but deepening it. It allows future generations to connect with history in more nuanced ways, supported by architecture that respects both memory and progress.

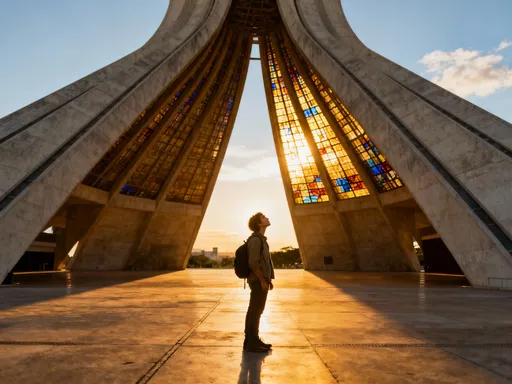

Griffin’s Vision and the Lakeside Pavilions: Hidden Gems with Modern Flair

Away from the grand institutions and ceremonial axes, Canberra reveals another side of its architectural character—one defined by subtlety and serenity. Around the shores of Lake Burley Griffin, a series of small-scale pavilions blend into the landscape with quiet confidence. These structures, often overlooked by first-time visitors, are testaments to the enduring influence of the Griffin plan. Designed for recreation, relaxation, and connection with nature, they reflect a philosophy that architecture should serve people and place, not dominate them.

Take, for example, the floating café at Aspen Island near the National Carillon. Its minimalist glass and steel frame appears almost weightless, hovering above the water’s edge. Large overhangs provide shade, while floor-to-ceiling windows dissolve the boundary between indoors and out. In the early morning, when mist rises from the lake, the building seems to float in a dream. Later in the day, sunlight dances across its reflective surfaces, changing its appearance with the hour. This responsiveness to environment is no accident—it is central to the design.

Other lakeside structures follow a similar ethos. Kayak rental kiosks, picnic shelters, and viewing platforms are built with clean lines, sustainable materials, and careful attention to orientation. They do not shout for attention; instead, they invite lingering. A mother and daughter might pause at a shaded bench to watch ducks glide by. A retired couple might sit on a timber deck, sipping tea and talking quietly. These moments of everyday peace are made possible by architecture that prioritizes human experience over spectacle.

What makes these pavilions remarkable is their consistency with the city’s original vision. Nearly a century after the Griffin plan was drawn, its principles still guide development. The lake remains a unifying feature, and the surrounding architecture enhances rather than overwhelms it. For travelers seeking calm amidst urban life, these spaces offer a powerful reminder that great design isn’t always monumental. Sometimes, the most memorable experiences come from the simplest structures—those that listen to the land and respond with grace.

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS): Culture in Concrete and Curve

Among Canberra’s most profound architectural statements is the building housing the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Unlike many government structures that impose form upon land, this building seeks harmony with it. Its design, shaped by consultation with Indigenous communities, reflects deep cultural knowledge and spiritual connection to Country. The structure is circular in form, echoing the significance of cycles, gathering, and continuity in First Nations traditions. This is not symbolic decoration—it is architecture as living culture.

The building’s orientation follows cardinal directions, aligning with ancestral understandings of space and time. Entryways face east, welcoming the first light of day, while internal courtyards open to the sky, allowing for celestial observation. Materials were chosen with care: rammed earth walls contain local soil, grounding the structure in place; timber ceilings evoke the canopy of ancient forests; and water features symbolize life and renewal. Even the path leading to the entrance is designed to slow the visitor’s pace, encouraging mindfulness before crossing the threshold.

Inside, the layout supports both research and cultural exchange. Quiet reading rooms, archival storage, and exhibition spaces are arranged to facilitate knowledge sharing in ways that respect Indigenous protocols. Digital archives are accessible in culturally appropriate formats, and community meeting areas are designed for elders and youth to gather comfortably. The building is not just a container for culture—it actively participates in its preservation and evolution.

AIATSIS stands as a model for how architecture can honor tradition while embracing modernity. It does not mimic ancient forms, nor does it erase them in favor of contemporary minimalism. Instead, it synthesizes both, creating a space that feels simultaneously ancient and new. For visitors, especially families interested in Australia’s rich Indigenous heritage, the building offers a rare opportunity to experience culture through space, light, and material. It is a place of learning, yes—but also of feeling. And in that emotional resonance lies its true architectural power.

Conclusion: Canberra’s Quiet Architectural Revolution

Canberra is not a city that reveals itself quickly. It does not dazzle with skyscrapers or clamor for attention. Instead, it unfolds slowly, like a story told in layers. What many dismiss as bureaucratic order turns out to be a canvas for thoughtful, meaningful design. From the bold geometry of the National Museum to the understated elegance of lakeside pavilions, the city’s architecture speaks in many voices—each one intentional, each one rooted in purpose.

This is not accidental. Canberra’s architectural strength comes from its foundation in long-term vision. Unlike cities that grow haphazardly, it evolves through careful stewardship. Every new building is measured not just by its aesthetics, but by its contribution to the public good, cultural memory, and environmental harmony. This creates a rare kind of urban beauty—one that is not flashy, but enduring.

For travelers, especially those who value depth over spectacle, Canberra offers a refreshing alternative. It invites you to look closer, to notice the curve of a roof that echoes a river’s flow, or the way sunlight hits a wall at a certain hour. It rewards curiosity with quiet revelations. You might come for the politics, but you’ll stay for the poetry of its spaces.

So if you’ve ever passed over Canberra on your travel list, reconsider. This is a city where architecture doesn’t just shelter—it speaks. Where every building, from the grandest memorial to the smallest lakeside shelter, carries intention and meaning. It is a capital not just of government, but of ideas. And in a world of fleeting trends, that kind of thoughtful design is worth the journey.